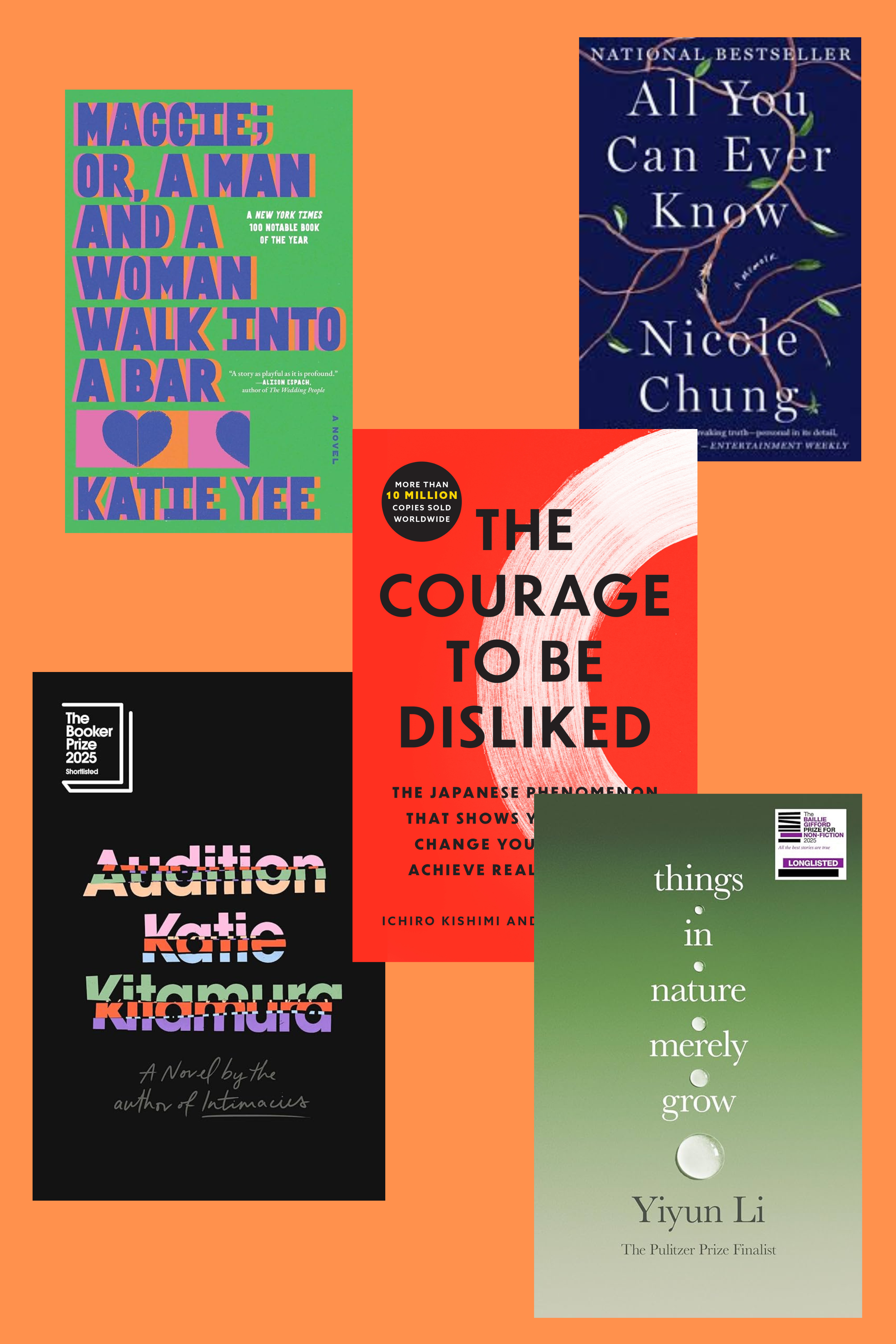

Asian American Psychologist’s Top 5 Books of 2025

Disclaimer! Not all of these books were published in 2025.

Maggie; or, A Man and a Woman Walk Into a Bar by Katie Yee

This novel is about a Chinese-American woman in an interracial marriage who faces grief and loss, illness, divorce, and other trials of adulthood and parenting. There’s no trauma here; one could say the problems presented are quite banal. And yet, I found this book to be moving and haunting. It layers emotions. The writing is subtle in how it captures the protagonist’s experiences in her immigrant family. By showing how things in the family were left unspoken but were nonetheless understood, the book helped me think about how explicit communication, which is a Western ideal, is not always necessary. But, as it happens to so many Asian American women in interracial/intercultural relationships, the default of “unspoken” takes a pernicious toll on the protagonist’s marriage. I appreciated that as imperfect and messy as the protagonist is, she displays a quiet self-acceptance rather than shame or the self-imposed pressure to “do better.” The writing itself is beautiful, with poetic Chinese folk tales and loving dialogues between a mother and her children. One of my favorite lines from the book is the following:

“They say the intensity of your emotions dulls with age, but the complexity of emotions increases—more mixed feelings, things that are bittersweet.”

All You Can Ever Know by Nicole Chung

This is a much lauded book that I’m late in discovering. It was published in 2018. It’s a memoir that explores the complexities of transracial adoption, identity, and belonging. Chung, a Korean American adoptee raised by white parents in a predominantly white community, chronicles her journey to find her birth family and reconcile the different parts of her identity. The book highlights some of the particular psychological challenges faced by transracial adoptees, such as the experience of growing up visibly different from one's family, navigating racial micro-aggressions without parental guidance, and the grief that can accompany adoptions even when the bond between adoptive parent and child is strong. What makes this memoir especially valuable for transracial adoptees is Chung's honest exploration of ambivalence and conflicts of loyalty, such as her love for her adoptive parents alongside her need to know her origins. Another example of her ambivalence is her gratitude for her upbringing alongside her anger at the racism she faced alone as a Korean child growing up in a white community. This is definitely a book that normalizes holding multiple truths simultaneously. Chung's narrative also speaks to the broader Asian American experience of feeling caught between worlds and the courage it takes to claim one's whole story rather than accepting the fragments others have offered. The following quote about the author’s experience of growing up in a white community with few people who looked like her moved me.

“To be a hero, I thought, you had to be beautiful and adored. To be beautiful and adored, you had to be white. That there were millions of Asian girls like me out there in the world, starring in their own dramas large and small, had not yet occurred to me, as I had neither lived nor seen it.”

The Courage to be Disliked by Ichiro Kishimi and Fumitake Koga

This book is modeled after Socratic dialogue and is intended to be didactic, which may not be everyone’s cup of tea. It presents Adlerian psychology through a series of dialogues between a sage teacher and a skeptical student. If you’re not familiar with Alfred Adler, he was a Jewish Austrian psychiatrist who was the founder of Individual Psychology in the early 20th century. Individual Psychology was a radical departure from Freud’s theories because it emphasized social and contextual factors for personality development. Although Alfred Adler’s name may not be in the popular zeitgeist today, his approach to psychotherapy is essentially infused in most contemporary forms of psychotherapy practiced all over the world. To say his influence was significant is an understatement.

The book's central premise is the Adlerian idea that we have the freedom to change and that our past does not determine our future. It makes sense to me why this book was a bestseller not only in Japan but also in many other countries. The book resonates particularly with Asian Americans who may feel trapped by familial expectations, cultural obligations, or the weight of intergenerational narratives. Kishimi and Koga argue that much of our suffering comes from seeking approval and living for others' expectations rather than pursuing our own life tasks, a message that can be both liberating and challenging for those raised in collectivist cultures that prioritize family harmony and social duty. The concept of "separation of tasks"—distinguishing between what is our responsibility and what belongs to others—provides a practical framework for setting boundaries without guilt, something many Asian American clients struggle with when navigating relationships with parents or extended family. While the book's emphasis on individual agency can feel a bit brutal at times and may require nuanced application in therapy, it offers valuable insights for clients working to differentiate their own values and desires from external pressures, and to build self-acceptance that isn't contingent on others' opinions. The quote below doesn’t do justice to the ideas in the book but is a good glimpse into the overall philosophy.

“Adlerian psychology is a psychology of courage. Your unhappiness cannot be blamed on your past or your environment. And it isn’t that you lack competence. You just lack courage. One might say you are lacking in the courage to be happy.”

And yes, after reading the book, I find myself more willing to risk being disliked. : )

Things in Nature Merely Grow by Yiyun Li

I’ll admit this was a hard book to get through. It’s a memoir about meaning in the aftermath of devastating loss. Li explores her experiences of losing her two young sons to suicide and her ongoing relationship with mental illness. From a clinical perspective, Li’s willingness to feel, examine, talk about unbearable pain is a brave public service. She does not for one moment pretend she can find resolution or closure, but she finds a workable co-existence with grief and loss. Many of my colleagues who specialize in grief work describe grief in similar ways—there is no “getting over it” but rather, a “living with.” I guess by reading this book, I feel I have permission to accept that some losses don't get better, they simply become part of who we are. I loved how Li's writing is spare and unsentimental.

Li shares the perspective she has developed on her sons’ suicides. It’s not necessarily an opinion about all suicides but I thought it was an interesting take:

“It seemed to me that to honor the sensitivity and peculiarity of my children—so that each could have as much space as possible to grow into his individual self—was the best I could do as a mother. Yes, I loved them, and I still love them, but more important than loving is understanding and respecting them, and this includes, more than anything else, understanding and respecting their choices to end their lives.”

These words have stayed with me and I continue to think about what they might mean. It’s a tough idea to reckon with, as a person whose profession, at minimum, is designed to prevent suicide. At the same time, I understand that we cannot always interfere with another human being’s agency and choices. My reading of this book also coincides with increasingly prevalent discussion about the role of mental health professionals in assisted suicide and the “Right to Die” movement.

Audition, by Katie Kitamura

This book is really strange, in a good way. I’m not sure I totally understood it. After I finished it, I told myself I’d read it again but I don’t have a great track record with that so it’s unlikely. But it’s remarkable that the feeling I had at the end of it was, “Let’s do this again.” It is so psychologically precise, like, in a way that made my brain kind of shiver with delight. For instance, the way people’s facial micro-expressions and bodily movements are described is downright forensic. I could really imagine what the person looks like in the movie version of the book playing in my mind as I read. I loved that. Details like this are really compelling and sharp. The story is unconventional, with everything getting upended about halfway through the book, which was confusing to me but after rolling with it, it made me think about what the story’s abrupt change says about the nature of performance and identity. Performance gets meta in this book because the protagonist is an actor and she is rehearsing a play while she is also evaluating her “performance” as a wife and a woman who is getting older. The observations were really interesting to me (as a woman who is getting older), such as the following lines about the unspoken truths about childlessness:

“People always talked about having children as an event, as a thing that took place, they forgot that not having children was also something that took place, that is to say it wasn’t a question of absence, a question of lack, it had its own presence in the world, it was its own event.”

Because of the topsy turvy plot, I questioned the protagonist’s grasp of reality. Maybe that was my clinical brain taking over too much. Although I don’t know if I fully understood the book, the question of who or what are we performing as “ourselves” in day to day life was an enjoyable and mind-boggling back-and-forth.